Please start this series of posts with blog #616

Equine conformation is the method of evaluating correctness of a specific breed's body proportion, bone structure, and musculature. While judging a horse's conformation, "form follows function" is considered: What is the animal's intended use? For instance, a Clydesdale is certainly not intended to be used in the same manner as the American Saddle Bred!

While researching a specific breed for sculpture subject matter, I refrain from slavishly analyzing strict conformation and typically experience the breed in its environment, up-close and personal. I pay attention to my first impression of the animal and what impressed me most. Afterwards and in the studio, I usually have a more analytical approach - particularly to proportion - while going over my sketches and photography. I also obtain all the information

and imagery I can in my library and the internet. . . I'm after the "look and feel" of the breed . . .

the GISS, or General Impression, Size, and Shape.

Below, is a great source of equine reference: The visible horse, purchased in a toy store.

Below, is a great source of equine reference: The visible horse, purchased in a toy store.

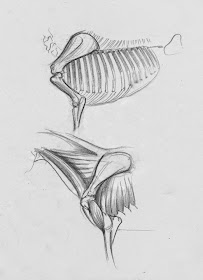

Below, is a sketch of my approach to basic equine proportion which was discussed in the previous blog.

I do not hesitate to exaggerate and/or distort proportion while seeking an artistic statement about the specific breed's conformation and proportions. For instance, making the waist of the Saddle Bred a bit smaller causes the animal to look more athletic and modeling the head of a Saddler slightly more refined creates a more elegant appearance.

A great place to experience the beautiful American Saddle Bred is a horse show.

I'm researching and planning a sculpture of a Saddler and below is an image of the horse's silhouette.

The American Saddle Bred - whether three-gaited or five-gaited - is an elegant horse with well-sloped shoulders,

flat croup, long and fine neck, and strong legs. Three gaits are natural to most horses: The walk, trot, and cantor.

The five-gaited horse must learn two more: The rack and the amble [also called the broken trot].

Whether bred for show or pleasure riding, the Saddler's conformation is stylish and proud.

The foremost quality that a Five-gaited Saddler must have when ridden in the ring is presence and flashy animation.

The judge looks for high action and high carriage of the head and tail. I never fail to get a lump in my throat when the show ring announcer shouts, "rack on!". . . the horse accelerates and goes faster and faster as the crowd goes wild!

The rack is a fast, smooth gait whereby the horse travels with each foot touching the ground separately to make four distinct beats. The horse must be trained to do the rack . . it's demanding and tiring for the horse but comfortable

for the rider. The Five-gaited is shown with long, flowing mane, while the mane of the Three-gaited is roached.

The rack is a fast, smooth gait whereby the horse travels with each foot touching the ground separately to make four distinct beats. The horse must be trained to do the rack . . it's demanding and tiring for the horse but comfortable

for the rider. The Five-gaited is shown with long, flowing mane, while the mane of the Three-gaited is roached.

Big draft breeds like the Clydesdale were useful on farms and pulling wagons with heavy loads and have been replaced with tractors. In towns, the nostalgic clopping of the Clydesdale can be imagined pulling carts piled high with beer kegs.

The Clydesdale's history dates from the 18th century and originated in Scotland. The breed evolved from the English draft horse and heavy Flemish stock and is not as heavy as other draft breeds such as the Shire, Belgian, or Percheron.

The Clydesdale has a distinctive style that is characterized by a brisk walk and stride. The neck is well arched with long shoulders and high withers. The back is short with well-sprung ribs and the strongly muscled hind quarters and legs convey an impression of strength and pulling power. The long, sloping pasterns are feathered at the rear of the legs below the knees, wrist, and hocks . . . most Clydesdales are either black, brown, or bay with white on the face and legs.

The Clydesdale has a distinctive style that is characterized by a brisk walk and stride. The neck is well arched with long shoulders and high withers. The back is short with well-sprung ribs and the strongly muscled hind quarters and legs convey an impression of strength and pulling power. The long, sloping pasterns are feathered at the rear of the legs below the knees, wrist, and hocks . . . most Clydesdales are either black, brown, or bay with white on the face and legs.

Below, is a recent bronze sculpture of a Clydesdale with tack entitled, "Horse Power".

Horse Power

There are many books about equine breeds and conformation . . . a good one is

"Storey's Illustrated Guide to 95 Horse Breeds" by Judith Harris Dutson;

Storey Publishing; 2005. Also available on Kindle.

There are many books about equine breeds and conformation . . . a good one is

"Storey's Illustrated Guide to 95 Horse Breeds" by Judith Harris Dutson;

Storey Publishing; 2005. Also available on Kindle.

Go to the BLOG INDEX and Reference Page for more information. See posts #616 and 655

Blog, text, photos, drawings, and sculpture . . . © Sandy Scott and Trish